Sheppie Abramowitz, a consummate political insider who became a powerful ally for refugees around the world, died on April 7 in Washington. She was 88.

Her death was confirmed by her son, Michael Abramowitz, who said his mother died at Sibley Memorial Hospital, from an infection and an aortic aneurysm.

For more than five decades, Ms. Abramowitz was active in movements to solve refugee crises — in Vietnam, Thailand, Turkey and Kosovo. With a firm, cajoling and unusually effective hand, she used her deep knowledge of government officials, logistics and the struggles of those fleeing war and oppressive governments, to secure real relief.

She was a diplomat’s wife — her husband, Morton I. Abramowitz, was a U.S. ambassador — and became his humanitarian adjunct, bringing her knowledge to bear when they returned to Washington from abroad.

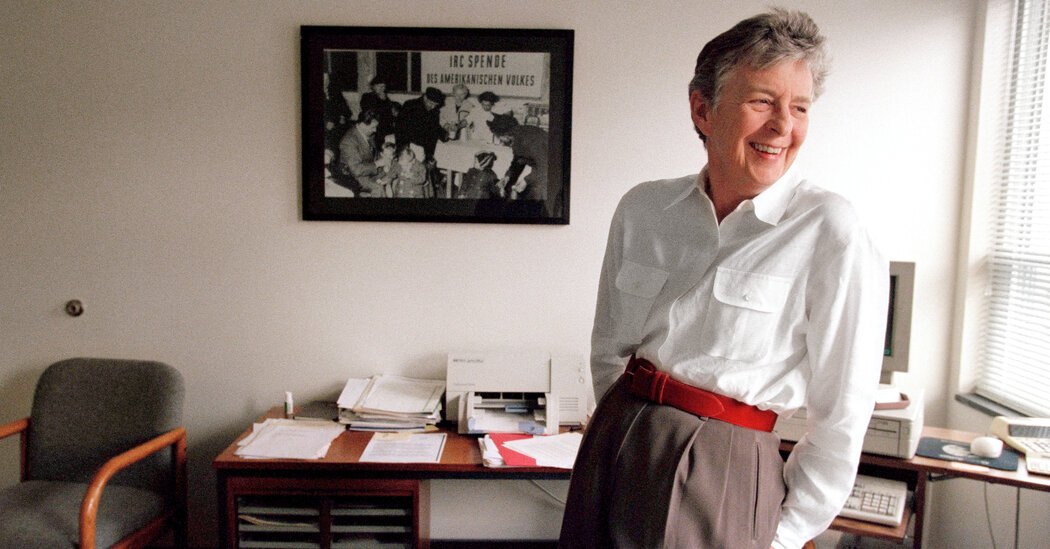

Ms. Abramowitz established a Washington office for the International Rescue Committee, one of the world’s leading refugee assistance organizations, and became a vice president. Even before that, she had long been a passionate voice for refugees, volunteering for the I.R.C. while her husband was posted in Hong Kong in the 1960s.

“Sheppie Abramowitz was an inspiration to generations,” David Miliband, the president and chief executive of the I.R.C., said on social media.

In 1979, she went to the Thailand-Cambodia border to visit refugee camps for victims of the Khmer Rouge, an experience that the former Treasury secretary Timothy Geithner, who accompanied her as a college student, described as “wrenching and shocking” in a recent email to her son. Her husband played a key role in persuading the Thai government to accept Cambodian refugees during his tenure as ambassador from 1978 to 1981.

The following decade, Ms. Abramowitz became the nongovernmental organization coordinator for the Bureau for Refugee Programs at the U.S. State Department, a role in which she became “a tireless cheerleader” for refugees, Gene Dewey, the former assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration, wrote in an email to her son.

She joined the I.R.C. in 1991. By 1999, Migration World magazine was describing her in a headline as a “crusader for refugees.” In an interview with the magazine, she spoke about the needs of Kosovo’s Albanian refugees, emphasizing the importance of security, shelter, sanitation and water projects as well as community medical assistance.

The publication called her “among a handful of officials who truly understand refugee issues at the field level and who can parlay that knowledge into helping effect policy.”

It added that Ms. Abramowitz used “a Rolodex thick with the phone numbers of diplomats, administrative workers, high officials and relief organization contacts” to help refugees and navigate the troublesome labyrinth of government red tape.

The plight of refugees “is a passion for both of us,” Ms. Abramowitz told the magazine, referring to her husband.

“Her defining role was to try to bend the U.S. political system toward a more moral, humanitarian approach to refugee problems,” Mr. Geithner said in an interview.

Ms. Abramowitz was not apologetic about using her insider status on behalf of refugees, telling The New York Times in 1999, “I’m shamelessly squeezing people I know in the administration.”

Sheppie Glass was born in Baltimore, on Dec. 17, 1935, the daughter of Benjamin and Ida (Gouline) Glass. Her father ran a record store downtown, and her mother was the librarian at a high school, Baltimore City College. Her mother was also a volunteer in helping to resettle World War II-era refugees, a passion that inspired her daughter.

Sheppie attended The Park School of Baltimore and graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a degree in history in 1957. The next year, she went to work for Representative Frank Coffin of Maine, a liberal Democrat, and she married Mr. Abramowitz, who was by then working for the State Department, in 1959. Soon after, Mr. Abramowitz was posted to Taipei, Taiwan, where they lived until 1963.

She later worked for Senator Edmund Muskie, Democrat of Maine, during his 1972 presidential campaign, a fact that was later held against her husband by Republicans who successfully blocked President Ronald Reagan’s attempt to appoint him ambassador to Indonesia in 1982.

While working in the State Department’s refugee office in the ’80s, she played a key role in ensuring that the federal government accepted as fact a controversial report on the murderous right-wing guerrilla group RENAMO in Mozambique, something that “never would have happened” without her intervention, the report’s author, Robert Gersony, said in a message to her son.

In 1994, when Mr. Gersony wrote a report pointing the finger at President Paul Kagame of Rwanda for his regime’s massacre of thousands of Hutus in the wake of the anti-Tutsi genocide, “Sheppie alone was standing up for me,” Mr. Gersony wrote.

Ms. Abramowitz retired from the I.R.C. in 2009.

In addition to her husband and son, Ms. Abramowitz is survived by her daughter, Rachel; her brother, Philip Glass, the composer; and three grandchildren.

In his eulogy for her, her son recalled both Ms. Abramowitz’s forcefulness and reach. The I.R.C. received a report that a wedding party in Afghanistan had been strafed by American aircraft. A colleague suggested submitting a report to the Pentagon.

“But Sheppie was having none of that,” he said. “She handed Mark” — the I.R.C. colleague — “the cellphone number for the deputy Secretary of Defense, whom she’d just seen at a party the previous night, and said, ‘Report it to him.’”