In the years he hid his sexuality from his children and village neighbors, Xiyadie would take short-bladed scissors to rice paper and give shape to unfulfilled dreams.

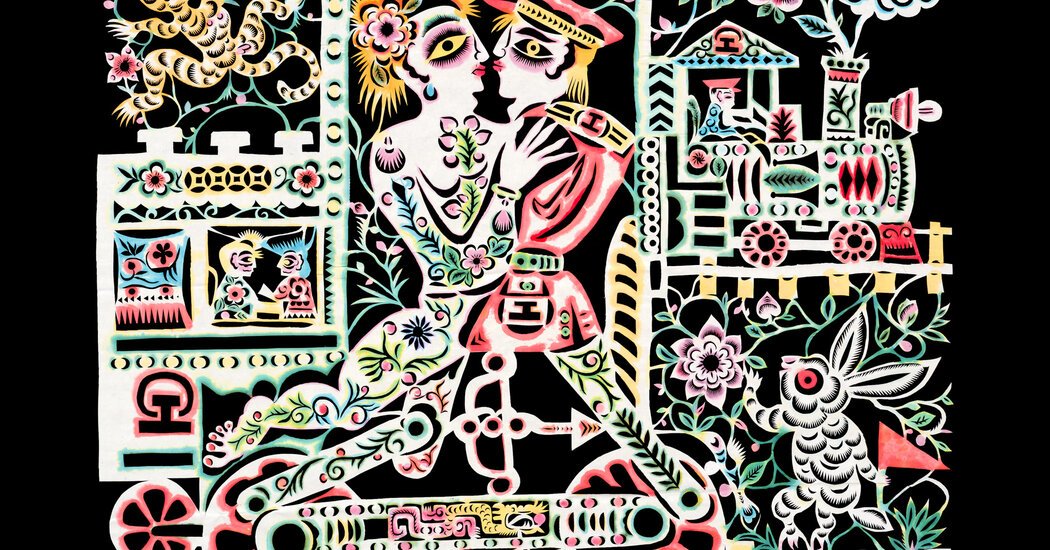

At first glance, his creations conform to traditional cutout designs of animals and auspicious symbols adorning doorways and windows in China. But a closer look at the shapes — birds, butterflies and blossoms perched on twisty vines — reveals bodies conjoined in the throes of intimacy or separated by brick walls.

The artist, 60, who goes by the pseudonym Xiyadie, was born in a farming village in northern China, and he creates queer paper cuts. Paper cutting is a folk tradition dating from the Eastern Han dynasty (25-220 C.E.) that involves cutting crisp lines and shapes into folded layers of rice paper. It’s about excising the negative space to reveal the picture inside.

Xiyadie’s home province of Shanxi was a hub for folk art; in his hometown, paper cuts marked births, weddings and Lunar New Year celebrations. The women in the village passed on the craft to their daughters and daughters-in-law. Xiyadie said he learned it by observing his mother and village matriarchs.

He mostly cut freehand, sometimes using indentations he made with his fingernails as outlines, then dyed his creations with green, pink, red and yellow pigments. He began making homoerotic paper cuts in the 1980s as he struggled with his closeted sexuality, but for many years he kept these works to himself.

Until 1997, gay people in China risked being persecuted; homosexuality was not removed from the official list of mental disorders, maintained by the Chinese Society of Psychiatry, until 2001.

“I put the feelings for men that I was not allowed to have into my creations,” he said in a phone interview.

In China, many artists who have found success have formal training from elite art academies, and the most visible queer artists tend to come from comparatively privileged urban backgrounds, said Mimi Chun, founder and director of Blindspot Gallery in Hong Kong. By contrast, Xiyadie creates elaborate scenes from his time as a closeted farmer and then as a migrant worker cruising in China’s capital city.

“He bridges folk art and queerness, and builds a dialogue between these two very disparate worlds,” she added.

The gallery will display more than 30 of his works in the show “Xiyadie: Butterfly Dream,” with an opening reception and an artist talk on Saturday. The show continues on Monday, and runs through May 11. The pieces connect different chapters in his life, including one of his first sexual encounters.

“Train” (1986) shows Xiyadie locked in embrace with a uniformed attendant, the figures’ legs moving in tandem with the coupling rods. A verdant backdrop surrounds them, as if to underscore the natural order of his tryst; a rabbit raises a victorious red flag in celebration.

“The flowers and leaves, the sun, moon and the birds are all part of my lingua franca — they convey my deepest thoughts,” Xiyadie said.

Xiyadie married a woman at the behest of his family, he said. They had two children, and their son was paralyzed by cerebral palsy. For some years, Xiyadie cared for the children at home while his wife worked at a hospital. The filmmaker Sha Qing documented the family’s struggles in a 2002 documentary, “Wellspring,” years before Xiyadie became known as an artist.

Xiyadie described the early years of his marriage as a charade he could not exit. Towering walls or doors separated his domestic life from his furtive trysts or fantasies. In “Sewn” (1999), he is trapped inside a house with a traditional tiled roof. While gazing at a photograph of his lover from the train (a recurring figure in his work), he sits atop a sword lying on its side and sews up his genitals, then pierces the roof with the giant sewing needle.

“I kept wanting to break through tradition and convention,” he said. “I wanted freedom. I wanted liberation.”

Years later, in 2005, he moved to Beijing in search of higher earnings and more artistic opportunities, discovering a vibrant gay community in the process. His family stayed in their hometown, but his son moved to live with him in 2013 for better medical treatment in the capital.

He began using the city’s cruising spaces as backdrops in his work, depicting dance-like trysts and ecstatic orgies in parks.

“Coming to Beijing, I felt like a frozen butterfly flying toward spring,” he said.

He gained a following among queer art collectors in Beijing, and his 2010 debut at the now-shuttered Beijing LGBT Center has led to exhibitions in Europe, Asia and the United States, including a 2023 solo exhibition at the Drawing Center in New York. The pseudonym he chose after he began to exhibit his art, Xiyadie, translates to “Siberian Butterfly,” referencing the drafty cold of his hometown and the resilience it takes to pursue freedom.

“From the beginning, I’ve cut butterflies,” he said. “It’s one of my strengths.”

In his work, he often gave himself and his paramours wings. It is also a dream he had held for his son, who could not walk and died in 2014. In “Hoping” (2000), one of the most poignant pieces depicting his family, his son rises from the confines of a wheelchair, sprouting wings, like a butterfly in metamorphosis.