The video posted last year on Chinese social media showed more than 100 Japanese children, supposedly at an elementary school in Shanghai, gathered in their schoolyard. Chinese subtitles quoted two students leading the group as screaming: “Shanghai is ours. Soon the whole China will be ours, too.”

The messages were alarming and infuriating in China, which Japan invaded during World War II. Except that the scene actually took place at an elementary school in Japan. And the students were not stoking hatred of China; they were swearing an oath to play fair at what looked like a sporting event.

The video wasn’t taken down until after it had been viewed more than 10 million times.

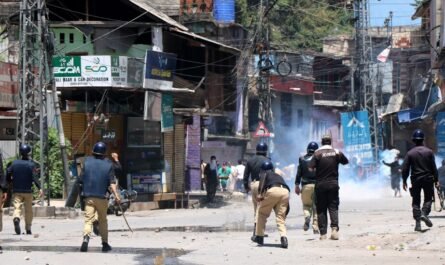

Xenophobic online content like the schoolyard video is the subject of debate in China right now. Last week, a Chinese man stabbed a Japanese mother and her son in eastern China. Two weeks earlier, four visiting instructors from a college in Iowa were stabbed in northeastern China. Some Chinese are questioning the role that online speech plays in inciting real-world violence.

China has the world’s most sophisticated system to censor the internet when it wants to. The government sets strict rules about what can and cannot be said about politics, economics, society and the country’s leadership. Internet companies deploy an army of censors. Private citizens censor themselves, knowing that what they post can get their social media accounts deleted or, worse, land them in jail.

Yet the Chinese internet is laden with hate speech toward Japanese, Americans, Jews and Africans, as well as Chinese who are critical of the government. False information about Japan and the United States regularly tops lists of popular searches and receives a ton of reposts and likes.

What is happening online is influenced by the rising nationalism that has been promoted in China under the leadership of President Xi Jinping. Mr. Xi has adopted a China-versus-the-rest-of-the-world mentality. One of China’s responses to worsening tensions with its rivals was “wolf warrior” diplomacy, a term used to describe an ultranationalistic and often hostile approach to geopolitics.

Of course, online hate speech and disinformation are not unique to China. But the Chinese government runs a well-oiled public opinion machine that tolerates and even encourages this kind of message when it’s directed at certain countries and their people. The authorities silence voices that try to correct the falsehoods or reason with their purveyors. The internet companies cash in on the online traffic that the chauvinistic content draws. And social media influencers, those at the grass roots and some of the most high-profile intellectuals and writers of the Xi era, get traffic and income.

In February 2023, the derailment of a train carrying toxic chemicals in East Palestine, Ohio, was covered extensively by Chinese state media. Influencers spun many conspiracy theories. One called the incident the equivalent of Chernobyl, the 1986 nuclear accident, and said it had left most of Ohio unlivable. The theory claimed that the U.S. government and the mainstream media were trying to cover it up, similar to what happened with Chernobyl.

Duan Lian, an online misinformation consultant who has 1.7 million followers on the social media platform Weibo, posted an article about the East Palestine tragedy that tried to separate facts from fallacies. He urged the public not to fall for misinformation. The article was reposted more than 1,000 times — and then it was deleted. His Weibo account was suspended for about three months, with Weibo citing violations of online regulations.

“The space for free speech has narrowed,” he told me in an interview.

Mr. Duan has been active on Weibo since 2010 and is known for his insightful work combating misinformation.

“In the past, if CCTV made a significant error in its reporting, you could mock it, right?” he said, referring to China Central Television, the state broadcaster. “But now, even if they blatantly lie, there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Liu Su, a science blogger in Shanghai, was censored for trying to set the record straight on a coordinated government campaign targeting Japan.

In 2023, China spread disinformation about the safety of the Japanese government’s decision to release treated radioactive water from the ruined Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the ocean. There were fear and outrage about what’s known in China as “nuclear-contaminated wastewater.”

After Mr. Liu wrote several articles challenging what was being said, someone reported him to the internet regulator in Shanghai. Mr. Liu deleted the article, posted an apology and promised to stay away from commenting on current affairs. Then his public WeChat social media account was suspended for six months.

Mr. Liu is one of a number of Chinese intellectuals who have voiced their concerns about the online condemnation of foreigners. In another article on WeChat this year, he criticized the trend of praising traditional Chinese medicine while belittling Western medicine. He was reported again.

“If the backbone of a society is completely submerged by the tide of nationalism, the future fate of the country is predictable,” he wrote.

China’s foreign ministry spokespeople said the recent attacks on foreigners were isolated crimes. The local authorities haven’t shared much information. But on social media, many comments praised the attacks and the perpetrators.

Another force for spreading online hate is a popular genre of short dramas on Chinese video platforms such as Douyin. In the videos, influencers stage scenes in which Chinese are humiliated by Japanese and then beat them up using martial arts moves. Or sometimes, a whole scene is just about insulting and beating Japanese people.

Anti-America sentiment is popular, too.

“I’ve been concerned for my two-plus years here about the very aggressive Chinese government efforts to denigrate America, to tell a distorted story about American society, American history, American policy,” Nicholas Burns, the U.S. ambassador to China, told The Wall Street Journal in an article last week. “It happens every day on all the networks available to the government here, and there’s a high degree of anti-Americanism online.”

It is telling to look at the times when Chinese censors act swiftly and effectively to remove something they don’t like.

In 2021, after the tennis player Peng Shuai accused a former senior national leader of sexual assault on her Weibo account, it took censors 20 minutes to delete the post and nearly all other posts about it. This is what’s known as a blanket ban.

A year earlier, to stop the Chinese public from talking about Mr. Xi, a social media platform censored 564 names that users had come up with to refer to him, including “a guy in Beijing,” “a big deal” and “the last emperor.” In 2016, a regulator gave a video platform a database of more than 35,000 terms about Mr. Xi that it wanted policed.

On Friday, Chinese people learned that a 52-year-old woman named Hu Youping, who had tried to stop the attack on the Japanese mother and son in eastern China, had died from her injuries. Many people mourned her on social media. Some said they wondered if the crime, targeting Japanese people, had anything to do with China’s nationalistic online environment.

In a rare move, China’s biggest internet platforms issued notices over the weekend that they were cracking down on hate speech that targeted Japanese and incited extreme nationalism. The questions are: How long will this continue? How much can it change an ecosystem that has been breeding hatred? And what will happen when it’s politically convenient for the government to use Japan and the United States as the boogeymen again? The notices themselves got many nasty comments.

“In this grand drama that plays out every day, some are directors, some are actors, some set the stage while the others are the audience,” wrote Peng Yuanwen, a former journalist. He called the attacker in last week’s incident a victim of nationalistic brainwashing. “He has become too deeply immersed in the play, finding it difficult to extricate himself,” Mr. Peng said.