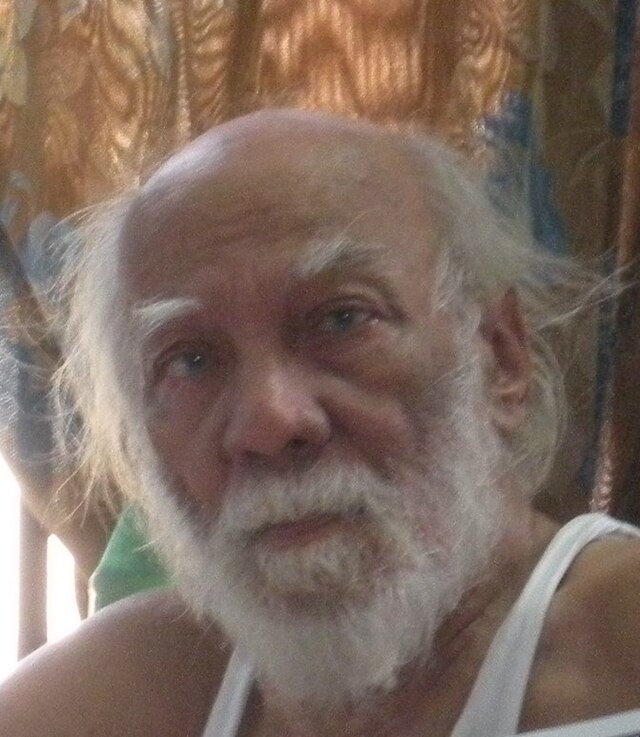

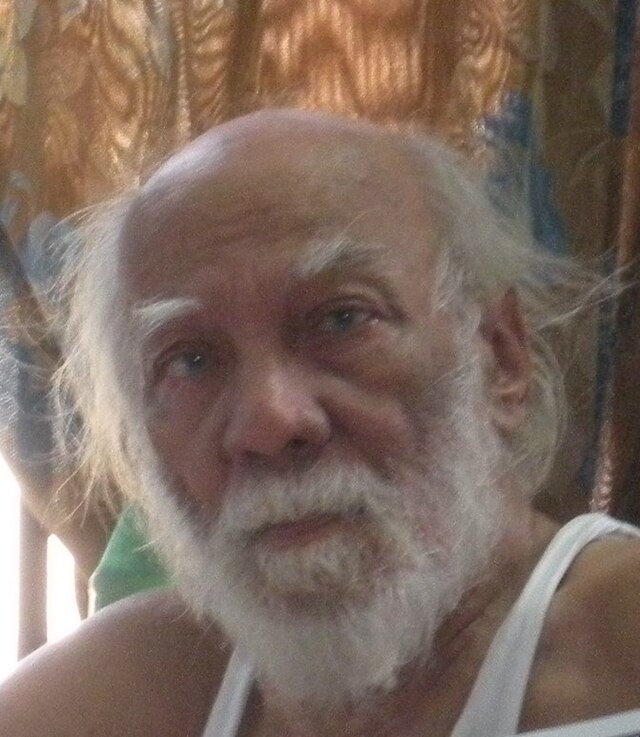

Badal Sircar, the Bengali playwright and director who revolutionised the Indian theatre movement in the late 20th century stepped on to 100 years on Monday July 15.. Hr was born in Calcutta in 1925 and in his 86 years of active life as a pioneer in the theatre movement in Bengal, he introduced a new stream of theatre making called ‘ Third Theatre’ which influenced a number of young theatre people from 1960s to the early 21st century..He passed away in Kolkata on May 13, 2011. .

The theatre in Bengal is known to draw men who were in diverse professions. Sircar followed in the footsteps of Girish Ghosh who was quite at home among the ledgers and journals not to forget other books of accounts in a merchant firm when he was not on stage as well as Sisir Bhaduri who left the college classroom as a renowned professor of English literature to put on grease paint, face the arc lights and became a legend. In Bengali theatre.

Sircar was a town planner having studied both at Bengal Engineering College, Shibpur and Jadavpur University. Thereafter, the similarities and otherwise between the three greats of the stage surface and end. If his plays which are talked about with reverence to this day, few know of Sircar’s ability to look into the future. He was a voracious reader during his school days, embraced Marxism in his own independent manner and actively supported the left movement during his early days.

Theatre did not let go of Sircar while he did not let it go. It was a forum to portray emotions, top most of which was protest. Not for anything were his plays considered “as the most rigorously non-commercial political theatre in India” as Rustam Bharucha chose to describe Sircar’s works. Throughout the 1970s, he together with Vijay Tendulkar, Girish Karnad and Mohan Rakesh spearheaded Indian theatre movement.

Sircar was a pioneering figure in street theatre as well as in experimental and contemporary Bengali theatre. He prolifically wrote scripts for his Anganmanch (courtyard theatre) and remains one of the most translated Indian playwrights. The central theme of many of Sircar’s early plays is an utter meaninglessness of our existence. It leads to a state of metaphysical anguish. Starting his dramatic career with comedies, he started a movement in the Indian theatre world, known as “Third Theatre”. Which was meant for masses and did not require any official funds or donations. The frugal expenses incurred in production could be managed from the common viewers themselves.

As a theatre director and a writer, Sircar tried to emancipate himself and his works. To achieve this end, he set boundaries and crossed them by bringing new ideas and methods from the West into Indian theatre. The cost of tickets were kept very low in Sircar’s plays. Local people and dignitaries flocked to the performance of his plays which did not rely on government funds or largesse from industrial houses.

One wonders whether the idea of stalls and galleries/balconies in theatres were abhorrent to Sircar as it reminded him of Roman amphitheatres where gladiators fought each other to death to the entertainment of the crowd. It would have been the last thing for Sircar, a man of the people to accept.

The Third Theatre was about the people. Sircar saw to it that it remained so manifesting the role, responsibility and rights of citizens. Works of Odin Teatret and Jerzy Grotowski were Sircar’s early inspiration. His first play in 1956 was Solution X based on the Hollywood film The Monkey Business. It was performed by people from his office called Rehearsal Group.

Sircar’s plays were marked by minimalistic use of sets, lights, costumes and even background music. Dance was experimented with and with it came ideas with movement, time and space rather than speech. Topics of Sircar’s plays range from man-woman relationships to social and political evils. If The Pleasant History of India, Stale News, Circle, Bhoma, Procession, The Mad Horse and The Whole Night were marked out by his directorial signature, the quintessential maverick reached the zenith of his creative powers in Spartacus and Ebong Indrajit.

If Sircar chose to stage Spartacus penned by Howard Fast and once banned in US, his direction gave the play centred round slaves revolt in ancient Rome, a burst of energy which struck a chord with the audience. For all his experimentation, he had a finger on the pulse of the crowd who appreciated it with spontaneous applause. The viewers saw in Spartacus some similarity with the political situation in the country.

This play about slaves, a marginalised community then and an exploited one too, triggers a desire to change. It sought to give a voice to the oppressed not only by representation of the script by characters but through form too. Undoubtedly Ebong Indrajit was Sircar’s magnum opus. It focuses on an author struggling with the writer’s block. He struggles to write a play but fails to do so and is unaware of the root causes. He finally finds inspiration in a woman, Manasi who is a representation of the Indian counterpart of Carl Jung’s concept of Anima. Questions are frequently asked in the play while Indrajit changes his preferred name time and again in it.

The play centres on Indrajit’s life, his compulsion to write together with his love and obsession with Manasi. Naxalite movement was at its height during the enactment of the play but Indrajit’s growing revolutionary leanings which go against society, is never under the wraps. Small wonder, to crush Indrajit’s spirit, the ruling class imposes rules. His travels to London and plans to kill himself though he is not capable of it, is a pointer about the futility of life and the roles played in society by men and women as creatures of circumstances.

Sircar seems to poke cruel fun at the middle class. Though he never denied of having belonged to this class, it emerges as one which has failed to adjust and ceased to aspire thereafter even as it is engaged in the daily struggle for survival. In his plays on middle class people of Calcutta, he made fun and showed how selfish and self centred the people were. He used his plays as a mirror to this class of people.

Sircar was an influential Indian dramatist and theatre director, most known for his anti-establishment plays during the Naxalite movement in the 1970s and taking theatre out of the proscenium and into public arena, when he transformed his own theatre company, Shatabdi’ (established in 1967 for proscenium theatre ) as a third theatre group . He wrote more than fifty plays many of which have been translated into different Indian languages and staged by the leading theatre groups of the states.

Sircar was awarded the prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship in 1971, the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 1972, Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1968 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship – Ratna Sadsya, the highest honour in the performing arts by Govt. of India, in 1997.The “Tendulkar Mahotsav” held at the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), Pune in October 2005, organised by director Amol Palekar to honour playwright Vijay Tendulkar, was inaugurated with the release of a DVD and a book on the life of Badal Sircar.

Badal Sircar influenced s a number of film directors, theatre directors as well as writers of his time. Film director Mira Nair in an interview mentioned, “For me, Kolkata was a formative city while growing up I learned to play cricket in Kolkata, but more than anything, I learned to read Badal Sircar and watch plays written by him for street theatre.” To Kannada director and playwright, Girish Karnad, Sircar’s play Ebong Indrajit taught him fluidity between scenes, while as per theatre director-playwright Satyadev Dubey, “In every play I’ve written and in every situation created, Indrajit dominates.” To actor director Amol Palekar, Sircar opened up new ways of expression. Badal Sircar’s plays are getting more and more attention from the theatre groups throughout the country as he turns hundred. (IPA Service)